OK, this is a cinematic tour de force by a maligned genius going berserk in the filmic toy store. Indeed. But, really, are you as nearly moved or astonished as you are simply impressed by all the ingenuity? This belongs on the list, but...Number One? The Post-Modernist in me says, um, no...

2. "The Godfather" (1972)

To learn of the extreme difficulties in its production is to marvel the film ever got made, much less, turn out as beautifully as it did. GII may be stronger stuff, but the sheer story-telling bravura of Coppola's (first) Corleone baby is something to behold, as we all watch it for the umpteenth time.

3. "Casablanca" (1942)

As perfectly assembled a cast and realised a Hollywood melodrama as ever was shot, with as hilariously a dysfunctional conception as The Godfather...and equally sublime a result, too.

4. "Raging Bull" (1980)

OK, aside from the gorgeous b&w photography and a clinic in Method madness, the adulation for this film eludes me. You would neither want to sit next to a single character in this film during a long plane ride than you would to have to watch it during the in-flight service...especially compared to Scorsese's eminently more accessible GoodFellas.

5. "Singin' in the Rain" (1952)

Even for haters of musicals, Donen-Kelly's vision of the MGM archtype is a joy to watch (and hear)...even after seeing A Clockwork Orange.

6. "Gone With the Wind" (1939)

Talk about Epic, in every sense of the word. One of the few such film examples that embody and surpass their literary origins, a touchstone for at least 3 generations of moviegoers that still commands attention almost 70 years after the fact. That's saying something, especially nowadays, when most Hollywood product struggles to do that 70 minutes after the fact.

7. "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962)

One of those indisputable "You MUST see this in a movie theater!" films (I know this, after years of TV viewings followed by a triumphant, freshly minted Los Angeles re-release), Lawrence works so well on so many levels, it's hard to imagine such a film being made today.

8. "Schindler's List" (1993)

Forget the girl in the red coat and a debatable ending - Spielberg's deeply personal unfolding of this small portraiture within the greater eternal horror of the Shoah is American film mastery at work. Considering American cinema's shameful half-century virtual silence on this crucial topic, it is a work whose time had long, long since come.

9. "Vertigo" (1958)

Ah, when movies were drawn from books that were actually worth reading. Not the most suspenseful or entertaining Hitchcock, but certainly the most psychologically complex and rewarding on a multiple-watching level. Pretty surprising to find audiences and critics didn't like it at all upon its initial release.

10. "The Wizard of Oz" (1939)

Another pitch-perfect MGM extravaganza that has endured like new through the years. The entire productions still looks and feels like new, an indelible footprint in the TV memories of millions of children.

11. "City Lights" (1931)

Chaplin's masterwork, in a career running a surplus of them. Certainly the zenith of silent movie-making, and one of the most genuinely, staggeringly human narratives ever committed to film. I can't believe Charlie thought his female lead was no good; his own performance reaches the perfection he so obsessively demanded in others.

12. "The Searchers" (1956)

The idea ANY cowboy film (besides for maybe Blazing Saddles) makes this list before a work by Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, or Renoir is a question that answers itself.

13. "Star Wars" (1977)

Do you remember watching this for the first time, and how you felt after walking out of the theater in 1977? Empire may be more dramatic, and the 2nd Trilogy longer, more expensive, and eye-poppingly more lavish - but this baby is still the most finely crafted and self-inclusive of the series. To think all of Hollywood turned it down; talk about "Stupid is as stupid does..."

14. "Psycho" (1960)

What must it have been like to see this shocker in a crowded theater in the twilight of the Eisenhower Era? Aside from the original Night of the Living Dead, could you name a more primal horror film? Let me ask you this - have you watched it alone recently?

15. "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968)

Too young to have partook of this, yes, masterpiece while under the influence, my generation still went and saw this in goodly numbers, mostly for the outer space visuals, which still look quite advanced. Now I watch it for the music as well as the sheer cinematic balls of Kubrick constructing a two-plus hour visual opera out of a one-line story. Unless you have a 5-star home theater system, don't even bother - the film deserves better.

16. "Sunset Boulevard" (1950)

Bitter bitter bitter, that Mr. Wilder...but never better. A true table-setter for that left field stream of daring, uncompromisingly dark films Hollywood gave to the otherwise desultory, conformist 1950's America. One suspects the Hollywood depicted here hasn't appreciably changed in the last half century, aside from the colors.

17. "The Graduate" (1967)

Still one of the smartest, funniest gems of an era rife with them, Nichols puts on a director's clinic that, like a lot (tho not nearly enough) of these on the list, is as knowing - and biting - today as it was when it came out.

18. "The General" (1927)

Chaplin's many silent works look like simple filmed vignettes compared to the complexity and breadth of Keaton's works, this one in particular. Something film students ought to study more.

19. "On the Waterfront" (1954)

Overwrought Commie melodrama, lol.

Arlene Greene writes: Where is Night of the Hunter? It stars Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, and Lillian Gish, and is directed by Charles Laughton. It's my all time favorite movie and I get chills just thinking about it. Some of the images from this movie are permanently etched in my mind-- a close-up of Mitchum's knuckles tattooed with LOVE and HATE, the bridal night scene with Mitchum telling Winters in no uncertain terms that he will not be sleeping with her sinful self, Gish in a rocking chair on the front porch, brandishing a rifle and singing "Bringing in the Sheaves" with the silhouette of Mitchum off in the distance on the road passing by verrrry slowly, the eerily quiet underwater scene of Winters with her hair floating around her face, and of course, the frog. The only criticism I have about this film is the ending, which is rather sugary and tied up with a bow -- rather a let-down after the emotional intensity of the rest of the film.

20. "It's a Wonderful Life" (1946)

Give me a break. Talk about overwrought holiday treacle. Give me A Christmas Story, Babes in Toyland, or Millions any day. I hate every frame, as would Mr. Barrymore's character, if he had to endure this cropping up on holiday TV schedules season after season, decade after decade, like an evil virus.

21. "Chinatown" (1974)

We studied Towne's script for this in film school, but I think it makes a better script to study than a film to actually watch, Nicholson, Dunaway, and Polanski's fine work aside.

22. "Some Like It Hot" (1959)

Good, naughty fun by a cast and crew clearly enjoying themselves. Perhaps Clooney and Pitt could see if they have the chops to doll it up and bend some gender. Who could replace Wilder at the helm, well, that's another story.

23. "The Grapes of Wrath" (1940)

Steinbeck is a drag, OK? Maybe his subject matter was, too, like Sinclair and Lewis, but that doesn't mean you have to like it. Henry Fonda is much more appealing when he isn't brought down by a morose part. Give me Modern Times or Sullivan's Travels for some '30's sociology.

24. "E.T. -- The Extra-Terrestrial" (1982)

Before any works of Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, or Renoir? Get real. I almost smacked a school chum who openly wept as we caught this on its opening day.

25. "To Kill a Mockingbird" (1962)

Attacus, Attacus...back when Hollywood embraced taking on social questions in a literate, adult sort of way. When dinosaurs ruled the earth, it seems.

26. "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" (1939)

Great stuff, but Top 100? Insert La Strada or Wild Strawberries here.

27. "High Noon" (1952)

See above.

28. "All About Eve" (1950)

I'm a bit embarassed, but I haven't seen it. If Roger Ebert says it's a Great Movie, then I'll bet it is, though.

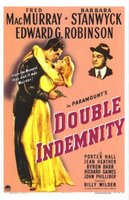

29. "Double Indemnity" (1944)

For those of us who grew up with Fred MacMurray as the father of My Three Sons, seeing him in this steamy noir classic is quite an eye-opener. Good dirty fun.

Felicia Florine Campbell writes: Certainly High Sierra (1941) is a far better choice for this list than, say, Forrest Gump. One of the first films done on location, High Sierra explores the Depression Era through its portrait of an honorable gangster, Roy Earle, played by Humphrey Bogart. In an era filled with corrupt politicians and cops, dust bowl farmers displaced from their farms by greedy bankers and endless bread lines, bank robber Earle stands above the others, an honorable man at odds with the system. Not quite a Robin Hood, his only victims are the oppressors and his betrayers. He is, above all, capable and honest within his context, betrayed by lesser men. He dies with dignity, the final scenes where he is hunted to his death in the Sierras as compelling as when they were filmed. Ida Lupino co-stars as his star crossed lover.

30. "Apocalypse Now" (1979)

May I submit to the AFI that this film is at least 25 slots below where it belongs? A case study in the dark side of moviemaking, yet, a creation of such cinematic - and artistic - magnitude as to exemplify the appellations. I believe this film will loom ever larger as the years pass, as the profound scope of this milestone comes into sharper relief amid the creative aridity of today's movie-making machinery. Number 30, my ass.

31. "The Maltese Falcon" (1941)

Bogie. The bird. The bong. 'Nuff said.

32. "The Godfather, Part II" (1974)

Consider: Francis Ford Coppola wrote, produced, and directed The Godfather, The Conversation, this, and Apocalypse Now in a nearly miraculous 7 year span. Wow.

33. "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1975)

Milos Forman is a fine, fine director, and the freak show cast of patients, many of whom would emerge in their own right, do, too...but Top 100? Sorry, Jack's unmedicated scenery inhalation just doesn't rock my boat to that degree.

34. "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937)

A genuine milestone in cinema that is also about thirty places too low. No child, of any age, has seen this and not long remembered the Evil Queen as one of film's most devilish devils.

35. "Annie Hall" (1977)

Well, only 35 places to get to Woody Allen. Still, in a list that omits Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, and Renoir...a walking -unspooling?- time capsule of '70's urban America (without the Scorsese grot) that is as side-splittingly funny as it is shrewd, cinematic, and magnificently bittersweet. Keaton's cover of 'Seems Like Old Times' sends chills up my spine, and nears inducing tears the second time around every time I re-watch this.

36. "The Bridge on the River Kwai" (1957)

Great, 'Good War' stuff from David Lean and a cast for the ages led by an immortal Alec Guinness.

37. "The Best Years of Our Lives" (1946)

Hollywood should have the guts to make such a film now, perhaps about our boys languishing at Walter Reed as we speak. Michael Moore must direct, too.

38. "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre" (1948)

Can you still hear Walter Huston's cackle, all these years later?

39. "Dr. Strangelove" (1964)

This may not be 'greatest' embodied, but have you ever been made to laugh harder and longer at characters and situations less humorous? One wonders if Kubrick and Peter Sellers, in a career performance(s), knew they were casting the die of all things Neo-conservative, fifty years before the fact?

Robert David Michael (Cerello) writes: Where is The Fountainhead? It stars Gary Cooper, Patricia Neal (in her film debut), and Raymond Massey as Gail Wynand. The work was directed by legendary talent King Vidor. Since movies are supposed to be fiction, it is my favorite film because it features arguably the most meaningful fictional - moral (worldly), ethical (self-responsible) - central character of all time, architect Howard Roark. It is also the only film in history (thus far) whose characters are motivated by mostly-explicit ideas. Its message - the near-impossibility of anyone's living a responsible and individual life within a nation without categories and regulations being in place to protect each man. The omission of this film, as well as Anthony Mann's Bend of the River, calls the entire list into fatal question.

40. "The Sound of Music" (1965)

I don't care if it made a fortune ("The sound of money," Darryl Zanuck said), this no more belongs on the list than Brigadoon, which is a lot more fun and better scored, besides. Zanuck hated it, too.

41. "King Kong" (1933)

All that money, footage, talent, and ballyhoo, yet, Peter Jackson's modern mess of a remake looks even messier when you savour the delicacies of this ground-breaking and nearly ancient masterpiece.

42. "Bonnie and Clyde" (1967)

What a treat to experience one of those rare gems that, to put it metaphorically, was a brick flying through the plate glass window of bourgeois American sensibilities, both commercial and social. It ain't just Warren and Faye goin' down in that there hail of bullets!

43. "Midnight Cowboy" (1969)

An X-rated film about a male hustler in an America rotting to its core, composed at a time when there was still a studio willing to produce it and an audience to go an see it. And it won Best Picture, too! Those were the days, indeed.

44. "The Philadelphia Story" (1940)

Cary Grant, Kathryn Hepburn, and Jimmy Stewart. If this were a cereal commercial with the same cast, it would still be a treat. Not entirely Top 100, tho.

45. "Shane" (1953)

I think I would've shot the kid. Speaking of Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, or Renoir...

46. "It Happened One Night" (1934)

Pre-code delights with still-valid pointers on how to hitchhike.

47. "A Streetcar Named Desire" (1951)

Forget the sordid family life that earned its hungered-for privacy in blood and all the physical excess - Brando was once a flesh-and-blood unbeknownst force of nature, and this is a good place to start to appreciate his singular talent.

48. "Rear Window" (1954)

I shanghaied a class of writing students into a revival of this, back when Las Vegas still had an art house movie theater, and they loved every minute of this Hitchcock thriller. You could feel them coursing with adrenaline as Raymond Burr raises his eyes across the apartment buildings and meets Grace Kelly's through the binoculars.

49. "Intolerance" (1916)

Before Greed???

50. "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" (2001)

If the criteria for this title's inclusion on this list is technical cinematic craft, then where is Barry Lyndon or Yellow Submarine? Uh huh.

51. "West Side Story" (1961)

For those of us who are not particularly entranced by the myriad of mythos regarding now vanished postwar NYC (or race-baiting casting practices), not much else to say. Except that I like Lenny's other compositions and Bob Wise's other films much more. My older sister's 8th Grade class was dragooned into seeing this for their class trip. Poor them.

52. "Taxi Driver" (1976)

Great performances in a sea of flotsam and jetsam, physical, psychological, and visual. Take the kids!

53. "The Deer Hunter" (1978)

Fine melodrama, with a admirable sense of the epic often attempted but rarely captured in post-'70's film. Of particular note for its unabashed love for its urban working class cast of characters, that nearly vanished species in the pop culture continuum. I'm looking forward to someone in Hollywood giving our current troops (and current disaster of a war) the same worthy canvas sometime soon.

54. "MASH" (1970)

Imagine that drearily milquetoasted TV sitcom with the same acidic black humour and punch-in-the gut near surrealism as Altman's big bopper. Fox ought to re-release it now, so maybe the kiddies could see what comedies were like when filmmakers made them for grown-ups who could both read and write. "...Goddamn Army..."

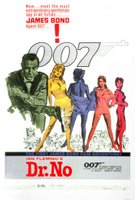

55. "North by Northwest" (1959)

This may not be 'great', but it sure rocks! It would make a great double-bill with From Russia with Love.

56. "Jaws" (1975)

Visceral, seat-of-your-pants moviemaking at its finest, with a score for the ages and all you need to know about how scary empty water can really be. And to think they didn't want Spielberg to direct it...

57. "Rocky" (1976)

Anyone who's ever dreamt of conquering an unconquerable dream (see: film school students, aspiring writers, kids in school sports) has to love this film, whether they respect the rest of Stallone's career or not (he's richer than you'll ever be; get over it and respect his wide success).

58. "The Gold Rush" (1925)

I am a huge Charlie Chaplin fan, but, my love for this aside, I don't honestly think this rates better than The Kid, Modern Times, or The Great Dictator.

59. "Nashville" (1975)

Having grown up in the same oddly muddled '70's this oddity mirrors, I'm still working on appreciating all the nuances and subtlties every reviewer cites in this Altman opus.

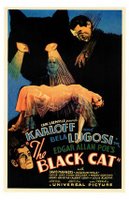

Adam Henry Carriere writes: Where are either Frankenstein or Dracula? Like virtually all such 'classical' horror films, these two genre-creating masterpieces from Universal remain touchstones of cinematic story-telling. The respective star-making performances by Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi continue to delight, as does the dramatic bravura of both, simply towering over anything else coming out of Hollywood in the early 1930's. Judge their greatness by the amazing loom of their long, dark shadows - from RKO's Val Lewton to AIP's Roger Corman, Britain's Hammer & Amicus Films to our own EC Comics, the rest of the Universal monster universe to Hitchcock himself...James Whale's Frankenstein and Tod Browning's Dracula are cinema greatness defined. Shame on the AFI voters for forgetting them.

60. "Duck Soup" (1933)

At last, an indisputable classic that is both amazingly modern (at least 30 years ahead of its time and as relevant as all hell now) and transcendantly hilarious. If this were the only Marx Brothers' film ever made, it would be enough. This is MY idea of a movie musical ;->

61. "Sullivan's Travels" (1941)

Again, perhaps not greatness, but damn fine, funny moviemaking with a heart as big as the America it squinted its eyes at...and possessing an inteligent, thought-provoking sense of the world, to boot. Try and find that at the cineplex.

62. "American Graffiti" (1973)

Were I older than 10 when this was first released, I'm sure the hyper-nostalgic gist of this would've better reached me, but just about every kid I know enjoyed it, just the same. I recently caught this on TCM, the first time I'd seen it in at least 20 years, and was plenty nostalgic all over again. Here is the USC grad George Lucas who got kidnapped on the way to the Federal Reserve just a few years later.

63. "Cabaret" (1972)

Oh, please. While a smoky, sleazy, sexy Weimar musical sounds good to me in the abstract, this closeted glam dross just ain't a great film, any more than Liza is a great female lead. Calling Lotte Lenya, Peter Lorre, and Fritz Lang!

64. "Network" (1976)

You think Peter Finch's heart attack, subsequent to his explosive performance here, constitutes 'leaving it on the field'?

65. "The African Queen" (1951)

Come on. Try Key Largo, instead.

66. "Raiders of the Lost Ark" (1981)

The 1981 Best Picture That Wasn't. Watch the exceedingly ordinary Ordinary People, then this, and tell me the Academy wasn't drug-induced by the political commissars of the Reagan Administration into voting for who they did.

67. "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" (1966)

Great Mike Nichols direction and vocal chord-shattering performances by Burton and Taylor, but 'greatest' cinema-making, this is not. Still a stagey play stagily committed to film.

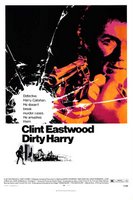

68. "Unforgiven" (1992)

One cowboy film I can stomach. And here I thought this list was giving short-shrift to Woody - here comes Clint in at...#68? Is the '81 Academy drawing up these lists? The whole of Shane and High Noon do not approach one frame of this elegiac noir gem or its near perfect cast. I'm not sure the genre has anything left to say after this one.

69. "Tootsie" (1982)

Smart, sassy, and pretty hilarious, if you see it...once. But, hey, I'm QUITE sure nothing Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, or Renoir ever did is as good as this, right? Right?

Joyce Corbett writes: Now Voyager is probably the most famous, most quoted and most admired film about female tyranny versus feminine freedom ever made. I suggest it should not have been dismissed by AFI's voters merely because its subject was "victimized females fighting back". The film, expertly directed by Irving Rapper, starred Bette Davis as a very repressed young woman, one who is aided by psychiatrist Claude Rains and falls in love with Paul Henreid, a married man. This is a beautiful, important and very artistic film; it certainly belongs, as Laura does, in the Top One Hundred Films' list.

70. "A Clockwork Orange" (1971)

A magnificently savage and bollock-rattling clinic in cinematic bravura, Kubrick's post-modern paradigm smasher hasn't aged a day since it rolled in the cash and notoriety over three decades ago. Ludwig van, Rossini, and Gene Kelly haven't been the same since, my brother.

71. "Saving Private Ryan" (1998)

To really gauge the impact of this dambuster, try watching nearly any war film (but perhaps 5 or 6 oddities) produced before and see if you're not mightily unimpressed as a result of this, arguably Spielberg's most accomplished work. The first 20 minutes alone display more craft, creative vision, and raw power than 90% of the genre. Too low, too low.

72. "The Shawshank Redemption" (1994)

Can an art house character study also be a soaring epic in the finest Hollywood tradition? Well, maybe not very often, but it is, here. Simply apply the Many Multiple Cable Showings Test - how often can you catch this, at any point in the film, and still be immediately pulled into it? Like many, my answer, regarding Shawshank, is probably every other day. At least 50 places too low.

73. "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" (1969)

Speaking of Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, and Renoir...I think Rules of the Game would be a nice fit here.

74. "The Silence of the Lambs" (1991)

The only horror film to win Best Picture - bloody revenge for Ordinary People, Shakespeare in Love, Chicago, and My Fair Lady! Oh, Sir Anthony...!

75. "In the Heat of the Night" (1967)

Right smack dab into a society convulsing in the civil rights struggle comes this sharply honed police thriller (and deserving Best Picture) from Norman Jewison and United Artists. Deeply discouraging how such timely explorations of living, breathing societal crises are utterly absent today, save for Michael Moore's work.

76. "Forrest Gump" (1994)

Great fx. Cool soundtrack. A USC film grad produced and directed. AND...as embarassingly self-congratulatory an orgy of narcissism committed to film for (and by) thems that know from narcissism: Ladies and gentlemen, I give you...The Baby Boom! Still, marginally worthwhile as a life lesson for 21st Century American careerists - the simpler if not dumber you are, the further you'll go.

77. "All the President's Men" (1976)

Crackling suspense in what you have to say is a minutia-based narrative that rather works against suspense, on the face of it. Ah, when journalism was still journalism, and major Hollywood movies were still designed for literate grown-ups.

78. "Modern Times" (1936)

Timeless and universal, heartfelt and hilarious, Chaplin's loving Valentine to the underprivileged working classes remains a gem.

79. "The Wild Bunch" (1969)

Were this produced today, it would run at least 45 minutes shorter and have at least triple the gunplay. But it wasn't, thankfully, and what's what is Peckinpah's signature work. (Older) William Holden and Robert Ryan were never better. I saw this in Hollywood revival with a twentysomething Japanese animator who had never heard of it, and he (and I) were rightfully astonished at the artistry going on here.

80. "The Apartment" (1960)

Um, I'm not so sure. How about a little Ozu or Kurosawa here?

81. "Spartacus" (1960)

Stanley himself would dispute this sand-and-sandal ballyhoo being on this list, certainly before or in lieu of Paths of Glory or Barry Lyndon. Maybe what this needs is Peter Sellers playing one of the Roman Senators. Or someone less...Brooklyn...playing Tony Curtis' role.

82. "Sunrise" (1927)

Me no see. Better had.

83. "Titanic" (1997)

Truth be told, I was thoroughly unimpressed when I saw this during its first run, noting that it took longer for the damn movie to unspool than it did for the actual ship to sink. A few years later, I rented this for no good reason and gave it the kind of close examination one can when stuck in a distasteful foreign country with nothing better to do than watch movies to death. Well, I found the work far more enjoyable the second time around, better appreciating the amazing levels of craft and storytelling on display. A Best Picture nod you can agree with on scope and success alone.

84. "Easy Rider" (1969)

This is pretty far down the list, considering the tectonic impact its vast box office success had on the industry during its then-current identity crisis. But at least it's here, so that's something. As delicious as guerrila filmmaking gets, offering a breathless, near hallucinogenic glimpse of the '60's cultural divide from ground zero. Too bad Fonda & Hopper didn't shoot the rednecks, instead.

85. "A Night at the Opera" (1935)

You'd have to know a bit about both the Marx Brothers and the mid-'30's MGM studio product to truly appreciate how remarkable their initial collaborations were. Critical to this was studio boss Irving Thalberg's strong hand in conceiving a closely-drawn (melo)dramatic template for the Marx bedlam to occur within. Opera queens rejoice - the film is a sheer delight. Allan Jones makes a pretty good Zeppo, too.

86. "Platoon" (1986)

I vividly remember catching an opening day afternoon matinee of this with a fellow graduate writing student. Exhilarated and emotionally drained, we both agreed it was by far the best picture we'd seen that year, and, lo and behold, Oliver Stone's first classic did in fact win the big one at the next Oscars. I've known a goodly number of men who were in country then, and all agree this film captures the truth of that steamy jungle portal to hell.

87. "12 Angry Men" (1957)

It speaks to Sidney Lumet's taut directing chops that what is essentially a one stage theater piece can be translated so energetically to the screen. Knowing his craft cold, from his lenses to his always expert casts, is part and parcel of Lumet's gifts. Sadly, his successor has yet to emerge.

88. "Bringing Up Baby" (1938)

Cute, fun, and light as a feather, but...

89. "The Sixth Sense" (1999)

Get real. Why not Blair Witch Project, too?

90. "Swing Time" (1936)

Good stuff, but...

91. "Sophie's Choice" (1982)

But...

92. "Goodfellas" (1990)

Perhaps the foulest mouthed mainstream classic ever made, not to mention riveting, joyous, remoreless, and scathing in equal parts. Scorsese clears the fences with this, the 1990 Best Picture That Wasn't.

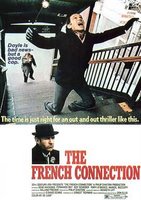

93. "The French Connection" (1971)

Speaking of Best Picture...One handy way to gauge an older film's transcendant qualities (assuming it has any) is to watch it like it were new, preferrably in a theater, with someone too young to have seen it when it actually was new. In this case, Friedkin's Cyclone ride of a picture show was new to myself and another film maven, having bailed from Bus Stop and ending up watching this by fortuitous default. We were both knocked out cold. 1971 Best Picture, indeed.

94. "Pulp Fiction" (1994)

I was on a reasonably hot date when I first saw this, so I was unable to appreciate the many complexities of the grand grotty guignol screenplay and the collection of performances that brought it to life. On cable, however, I see it all...but still prefer Jackie Brown as a much more cohesive overall Tarantino achievement.

95. "The Last Picture Show" (1971)

Like Nashville, I'm still working on this, but adore the raw b&w photography.

96. "Do the Right Thing" (1989)

Why does this look and feel like a token add-on to this list? Great, attention-grabbing stuff, but not really Spike's best. It is, however, about a thousand times more vital and compelling than Driving Miss Daisy, which took the big Oscar that year. Spike was right then and he's right now: Miss Daisy is everything you need to know about Hollywood's view of Black Americans.

97. "Blade Runner" (1982)

A science fiction film milestone that still looks and feels new, minus CGI. One of Harrison Ford's best performances.

98. "Yankee Doodle Dandy" (1942)

Not before Frankenstein and/or Dracula, babe.

99. "Toy Story" (1995)

A lot of lesser 'critics' (movie-watchers, really) throw around the phrase "The film that changed it all!". Well, this one actually did change animated movies, and pretty much for the better, technology-wise, anyway. For us old skoolers, tho, Yellow Submarine or even The Triplets of Belleville still rate higher, even if they didn't make nearly as much money.

100. "Ben-Hur" (1959)

Take away Yak Canutt's show-stopping chariot race and Gore Vidal's crypto-queer Stephen Boyd character and there isn't much else here, aside from what Vidal hilariously refers to as Heston's uncontrolled channeling of Francis X. Bushman. At least Gladiator didn't squeeze in here.

...compiled by Adam Henry Carriere